Silk is a protein filament extruded by the larvae of insects, most especially the silk moth Bombyx mori. The moth takes its name from the mulberry leaf on which the larvae feed (Morus is Latin for mulberry). Each larva creates two filaments (fibroin), stuck together by silk gum (sericin) to form its cocoon. The silk filament is reeled from cocoons after the larvae’s development has been stopped. (Some cultivated silk larvae are allowed to develop and emerge as moths for the next year’s egg production.) Warm water is used to loosen and unreel the filament fiber, which includes the gum as well as the silky filament at this stage. The gum is then removed by varying degrees, and at varying stages of production. Silk filament without gum is white; the gum gives the filament an ecru color. The filaments from a single cocoon of one silkworm are on average a mile long, and are strong, glossy and resilient.

Here's a 19th-century image of a Japanese woman reeling silk on a zakuri (silk reel):

Double cocoons, or ones that became intertwined when the larvae are spinning them, unreel unevenly, with thicker spots in the filament. This type of silk fiber is suitable for weaving doupioni silk, shantung and pongee, where the thick spots show as slubs in the texture.

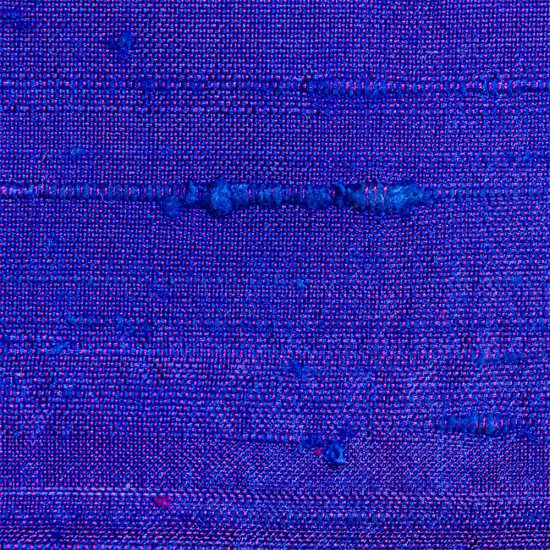

Here are examples of doupioni silk:

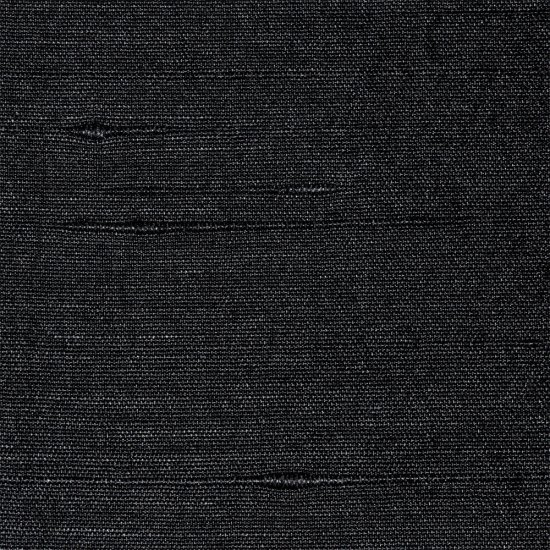

shantung:

shantung:

and pongee:

and pongee:

The silkworm moth, Bombyx mori, can’t now survive in the wild after being domesticated for such a long time; it is neither camouflaged nor able to fly. Silk fabric is also produced from wild moth larvae, most notably those of the tussah moth. This wild silk is of a very different style and quality.

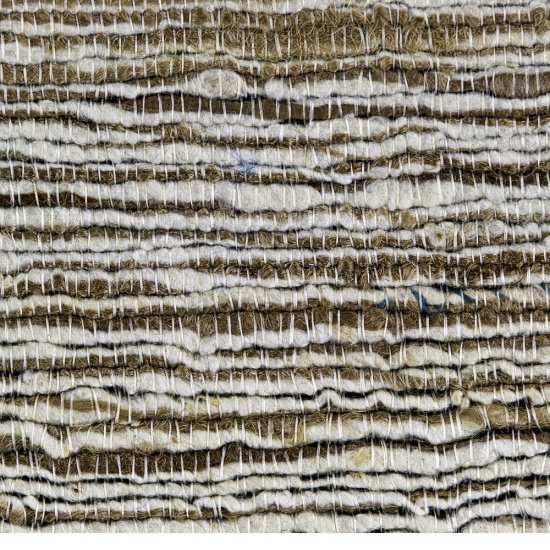

Here is an example of tussah silk:

In the long history of silk culture (sericulture), China has always been king. The use and cultivation of silk dates from at least 3500 B.C.E. there.

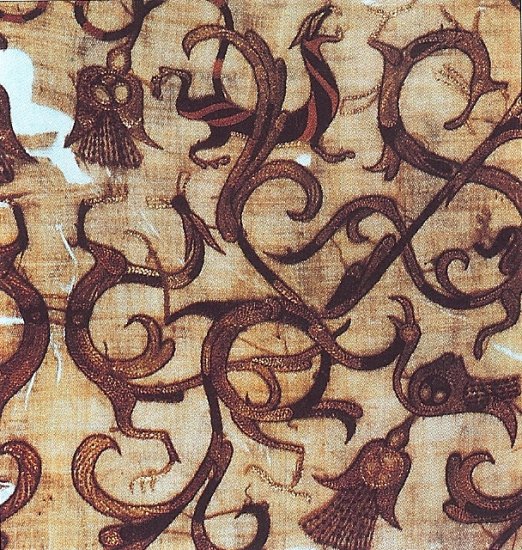

This is an embroidered silk gauze dating from 4th-century B.C.E., Zhou Dynasty, China:

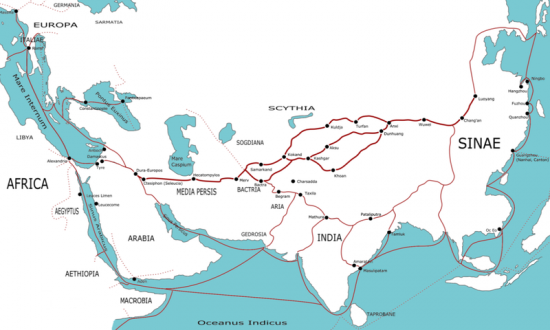

The lucrative silk trade reached India, Europe, Africa, the Middle East and North Africa along what was known as “The Silk Road,” beginning during the Han Dynasty (around 200 B.C.E.). For centuries China carefully guarded its silk production method. Silk cultivation was smuggled into Byzantium ca. 550 C.E., and by the 14th and 15th centuries Italy had become known for its fine silks, followed not long after by France and England. At this point China is by far the largest producer of silk, and this not only follows from China’s history of production but also from its relatively large low-wage work force—silk production is labor intensive.

If you want to go down a very deep rabbit hole, the Silk Road is a fascinating subject. It was not just a trade route for silk, spices and other commodities, it has been described as the vascular system of culture. From a University of Oregon class (Life on the Silk Road) description: "Italians learned Persian for better bartering, Mongols crowded to hear the bright melodies of Chinese flutes, and travelers who braved the harsh cold of the Pamir Mountains met with awe the nomads who called the unforgiving peaks their home."

Remember how there are two types of fiber, staple and filament? Filament is the long one, often measuring hundreds of yards in length. Silk is the only natural filament fiber, but manufactured fibers always start as very long fibers and can be cut as needed. Filament fibers make smooth, strong yarns.

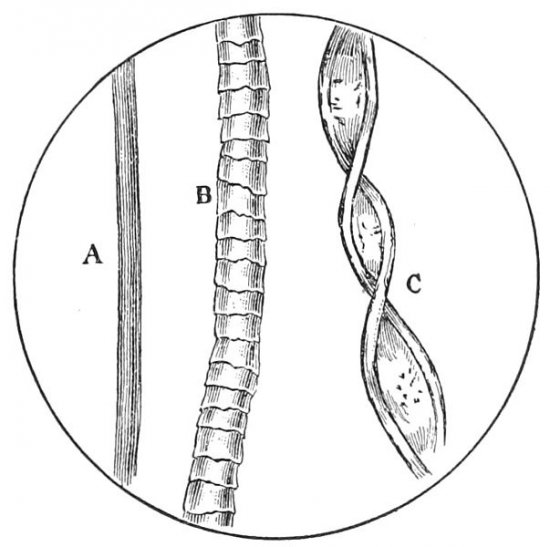

Here is what a silk fiber (A) looks like magnified, next to wool (B) and cotton (C). It's very fine, strong and smooth.

Many fabrics were originally always woven from silk: Satin, damask, brocade, chiffon, georgette, charmeuse, crepe de chine, gazar, organza, faille, taffeta, and more. You can always look through fabrics by fiber in the Fabric Resource. Here are the silk fabrics: https://vintagefashionguild.org/silk-or-silk-like/

I also want to mention the waste from silk production. A noil is a short fiber that is removed from a yarn in the process of combing. Although they might be considered waste, noils can be used for filling material such as padding, or they can be spun into yarns. Silk noil is made from the noils left over from preparing filament silk.

This is an example of silk noil:

I'll spare you the details of culinary use of silk pupae—being a vegetarian, that's not my cup of tea.

Let's have some questions and comments, please!

Here's a 19th-century image of a Japanese woman reeling silk on a zakuri (silk reel):

Double cocoons, or ones that became intertwined when the larvae are spinning them, unreel unevenly, with thicker spots in the filament. This type of silk fiber is suitable for weaving doupioni silk, shantung and pongee, where the thick spots show as slubs in the texture.

Here are examples of doupioni silk:

The silkworm moth, Bombyx mori, can’t now survive in the wild after being domesticated for such a long time; it is neither camouflaged nor able to fly. Silk fabric is also produced from wild moth larvae, most notably those of the tussah moth. This wild silk is of a very different style and quality.

Here is an example of tussah silk:

In the long history of silk culture (sericulture), China has always been king. The use and cultivation of silk dates from at least 3500 B.C.E. there.

This is an embroidered silk gauze dating from 4th-century B.C.E., Zhou Dynasty, China:

The lucrative silk trade reached India, Europe, Africa, the Middle East and North Africa along what was known as “The Silk Road,” beginning during the Han Dynasty (around 200 B.C.E.). For centuries China carefully guarded its silk production method. Silk cultivation was smuggled into Byzantium ca. 550 C.E., and by the 14th and 15th centuries Italy had become known for its fine silks, followed not long after by France and England. At this point China is by far the largest producer of silk, and this not only follows from China’s history of production but also from its relatively large low-wage work force—silk production is labor intensive.

If you want to go down a very deep rabbit hole, the Silk Road is a fascinating subject. It was not just a trade route for silk, spices and other commodities, it has been described as the vascular system of culture. From a University of Oregon class (Life on the Silk Road) description: "Italians learned Persian for better bartering, Mongols crowded to hear the bright melodies of Chinese flutes, and travelers who braved the harsh cold of the Pamir Mountains met with awe the nomads who called the unforgiving peaks their home."

Here is what a silk fiber (A) looks like magnified, next to wool (B) and cotton (C). It's very fine, strong and smooth.

Many fabrics were originally always woven from silk: Satin, damask, brocade, chiffon, georgette, charmeuse, crepe de chine, gazar, organza, faille, taffeta, and more. You can always look through fabrics by fiber in the Fabric Resource. Here are the silk fabrics: https://vintagefashionguild.org/silk-or-silk-like/

I also want to mention the waste from silk production. A noil is a short fiber that is removed from a yarn in the process of combing. Although they might be considered waste, noils can be used for filling material such as padding, or they can be spun into yarns. Silk noil is made from the noils left over from preparing filament silk.

This is an example of silk noil:

Let's have some questions and comments, please!