And the conservators report:

CONSERVATION/RECONSTRUCTION RECORD

Object: Original British Grenadier's Mitre, 1727-1743

Date: 30 May 2013

Inferred Provenance: see Artifact Interpretation

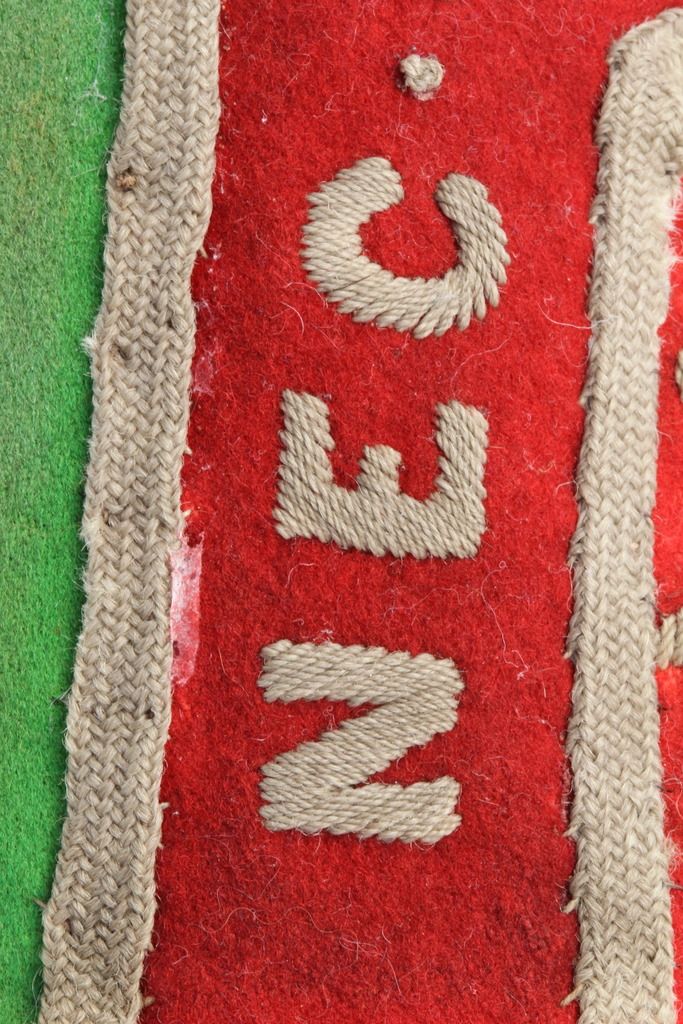

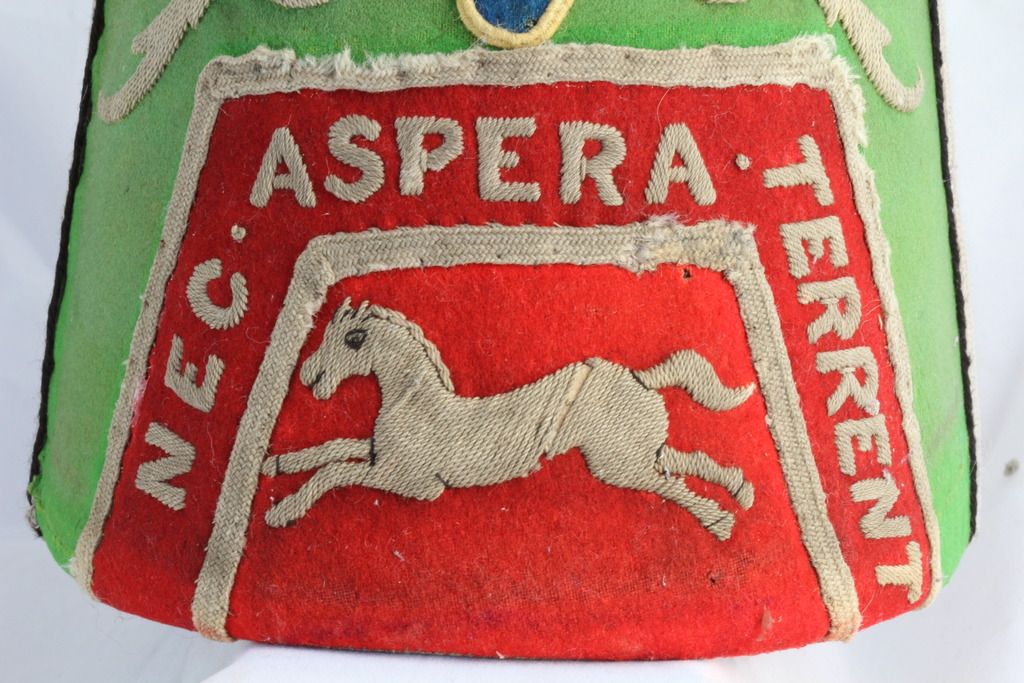

Artifact Description: Green woolen mitre, with extensive, artful hand embroidery, woolen lace, woolen soutache, and puff-pompon. Body is constructed of an almost lime-green, doeskin-finished facing wool, of high quality. Embroidery is executed in off-white cable-laid silk upon a cardstock cutout base/filler to add relief. Frontal ornamentation consists of a British imperial crown, flanked by scrollwork; a blue woolen applique representation of the Order of the Garter with embroidered motto “Honi Soit Qui Mal Pense,” bordered by lemon yellow soutache, and with a scarlet woolen circular center bearing the silk-embroidered initials “CR;” a lower panel of scarlet wool bordered by tubular woolen lace, bearing the embroidered motto “Nec Aspera Terrent” and bordering—on three sides—an embroidered representation of a galloping horse. Rear ornamentation consists of a bottom panel with more high-relief scrollwork, and black-bordered off-white woolen flat lace covering all sewn seams. Pompon is of off-white woolen yarn, with no core, stitched at mitre's apex. Cap's interior is a mass of sheet cork fragments, shredded polished cotton, and two types of disintegrating cotton sateen. Condition overall is poor. All woolen fabric and embroideries are infused with and discolored by coal dust and other particulates, and most seams are coming apart. Some color bleeding from scarlet lower panels. Woolen lace is shredded at high points and in many other areas, with a patch of lace entirely missing above the “Nec Aspera” motto. Interior is a near-incomprehensible and filthy mass of fragments and shreds.

All original seams--both structural and for affixing ornamentation--are handsewn with both silk and cotton thread. Some seams on replacement components (see Artifact Interpretation) are handstitched, while others were executed on a sewing machine. The cap's structure and layout points to subcontracted work, including professional embroidery followed by inexpert cottage assembly. The latter manufacture was tackled by one who was likely numerically illiterate: nothing in the cap's assembly is symmetrical, and all measurements appear to have been “eyeballed.”

Artifact Interpretation: Classic British military mitre, worn by a member of the Grenadier Company, 2nd “Queen's Own” Regiment of Foot, manufactured between 1727 and 1743. Reid and Hook in British Redcoat, 1740-1793 (London: Reed Books, [Osprey Warrior Series], 1996) offer a nutshell view of the martial mitre's development: “Originally the mitre was simply a stocking cap with a small turn-up at front and rear--the 'little flap,' but by the 1740s the whole cap was stitched together and a degree of stiffening provided for the now combined front and 'little flap,' in order that the cap stood upright. It

appears, however, that this attempt to smarten it up was frustrated by the grenadiers'

CONSERVATION/RECONSTRUCTION RECORD--30MAY13, p. 2 of 5

continued insistence on jamming it on to their heads as though it was still the stocking cap that had been adopted by assault troops in the previous century as a more practical alternative to the wide-brimmed hat.” Eventually, the “degree of stiffening” mentioned was rendered more rigid by the addition of an interior framework of cardboard and cane, and this piece is likely one of the earliest examples extant which was originally crafted with that structural refinement.

Fairly accurate dating is permitted by one of the cap's frontal ornaments. The “CR” initials within the Order of the Garter representation are for Caroline Regina—Caroline of Ansbach, who ascended the throne in 1727. Previously, Caroline was the Princess of Wales, and her namesake regiment was styled “The Princess of Wales Own Regiment of Foot.” In 1727 the unit was renamed, for obvious reasons, “The Queen's Own Regiment of Foot.” The upper end of the dating bracket is provided by the Royal Warrant of 1743, which decreed that thereafter all grenadier mitres would bear the initials of then King George (previous to this regulation, regimental commanders were free to mandate whatever they wished to decorate their regiments' fusilier and grenadier cap's fronts in the cypher's location). This pattern of mitre was completely supplanted in service by the bearskin adopted under the Warrant of 1768. Hence, this cap could only have been manufactured between 1727 and 1743, though its use may have continued for a year or two past the 1743 Warrant.

The motto of the Order of the Garter, “Honi Soit Qui Mal y Pense,” is French, and is variously interpreted as “Shamed be he who thinks evil of it,” and “Shame on him who thinks ill of it.” The other motto, “Nec Aspera Terrent,” in the squared arc above the galloping horse, is Latin, and interpretations in military usage can wax ridiculous. The most commonly accepted by scholars are: “Difficulties be damned,” and “Nor do hardships terrify.” The running mount is the Hanoverian Horse, imported to Britain along with the monarchs of that house. The horse and “Nec Aspera” motto were more or less standardized--fixtures on most, if not all, British mitres of the 1740s. Not so universally used was the heraldic “wreath”, representing an elongated twist of black and yellow cloth typically seen atop medieval helms. This device sometimes provides the ground upon which the Hanoverian Horse runs, but there was absolutely no evidence of its presence on this mitre.

The Queen's Own Regiment enjoyed a tranquil eighteenth century, with its London-based garrison duty interrupted only by rare musters to suppress the occasional riot. Perhaps such local service explains this mitre's survival--and in relatively good condition. However, the piece experienced a period of secondary usage, either as a displayed artifact or--far more likely--worn in regimental Tradition Ceremonies in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. This history is well-chronicled through interpretation of the cap's interior lining and other modifications.

When targeted for re-use, perhaps 125 to 150 years after its original service life, the mitre was refitted at a military milliners, probably in London. At that time, its original strawboard-and-cane interior framework and original lining had likely deteriorated, and the military hatters removed it. They crafted a replacement front-stiffener of sheet cork (as used in the manufacture of Victorian tropical and fulldress helmets) and substitute interior lining of polished cotton and cotton sateen (typically employed in that era's uniform linings). All these materials would have been commonplace--and inexpensive--in any uniform supplier's shop of the period. The cotton fabrics formed a two-layer lining, machine-sewn into a basic bag-shape, then anchored by handstitching through some portions of the front's ornamental panels and along its lower border. At the same time, the hatters attempted to render the cap more symmetrical in appearance by folding under the lower portion of the front panel. This modification did level the “Nec Aspera” panel, but also concealed the final “T” in “Terrent.”

CONSERVATION/RECONSTRUCTION RECORD-, 30MAY13, p. 3 of 5

Significantly, the milliners also trimmed away the now-excess original green and scarlet fabric--a band perhaps 3/4” wide--along the cap's bottom as part of this effort at symmetry. After the reconstruction, most of the cap's wear--including some bleeding of the non-colorfast scarlet fabric at the mitre's bottom (positioned against a wearer's brow)--appears to have occurred in this period of secondary use.

Tertiary use was evidently as a display item, likely in a home, then retirement to storage. And these dispositions occasioned a final, superficial modification to the mitre, plus more deterioration. Perhaps sometime after Victoria's reign, the cap's cork stiffening began to disintegrate--which is typical for aged sheets of this material. As a stopgap, evidently in an attempt to keep cork fragments from littering the home's mantlepiece, someone who was not adept at sewing handstitched a short black cotton sateen bag to the mitre's lower edge. (By the time the cap was received for treatment, this century-old addition had also begun to fall apart). Once the cap became too disreputable for display, it was retired to an attic or basement in a structure utilizing coal for heating. Lying face-up on a horizontal surface, the mitre became infused with coal dust and soot, permanently discoloring all surfaces--but especially its front. The presence of sulfuric acid in this environment faded the bright green and rotted the cap's handstitched seams, as well as the stitching securing lace trim. Too, it appears to have rendered the single layer lace brittle, and prone to disintegration. Remarkably, the woolen facing fabric, as well as the woolen yarn pompon remained rot-free, though discolored.

When examined for treatment, and especially once the several layers of intrusive lining were removed, it became readily apparent that the only possible course for restoration and reconstruction would be separation of the cap into its component parts and complete rebuilding--in as gentle and unobtrusive a fashion as possible.

Treatment Details

Note: All materials employed in conservation and reconstruction were of museum/archival quality, including filtered water, and pH-neutral soaps, paints, varnishes, and adhesives. All thread used in restoring the cap was pure cotton and silk, usually of pre-WWII vintage. Wherever use of materials is mentioned, we will avoid redundancy, and permit the reader to infer “archival quality” or “pH neutral.”

Condition: Cap interior littered with cotton fabric swatches and cork fragments.

Action: Remove all intrusions, documenting the removal of layers via photography, and archiving the salvaged materials for retention by owner.

Condition: Thread securing structural seams rotten, seams failing.

Action: Remove remaining threads and disassemble cap. Archive all retrieved thread fragments.

Condition: Thread securing ornaments is rotten, appliques and lace are in danger of falling off cap.

Action: Remove ornaments and pompon, archive thread fragments, and document disassembly with photographs.

Condition: All components soiled with coal dust and other contaminants.

CONSERVATION/RECONSTRUCTION RECORD, p. 4 of 5

Action: Test for colorfastness. Handwash colorfast green woolen fabric and undyed pompon with pure soap and rinse. Rinse non-colorfast fabrics, including the scarlet and blue facing materials in mineral spirits. Note: multiple rinsings were employed, whether of filtered water or mineral spirits.

Condition: Regimental lace--consisting of a 3/8” off-white woolen strip, bordered on one side with a woven-in black yarn “worm” on one edge—is tattered, frayed, and incapable of consolidation or longterm preservation. [Owner consulted.]

Action: Craft replacement lace, of authentic 100% woolen tape, bordered with handstitched black Angora yarn, and overdye a light pearl gray to match the color of other previously-white components.

Condition: Lemon yellow soutache bordering Order of the Garter insignia disintegrated upon removal from cap.

Action: Overdye replacement soutache of authentic 100% wool in correct lemon yellow hue.

Condition: Tubular lace bordering “Nec Aspera” motto frayed in several locations; missing portion at right, above running horse.

Action: Secure frayed portions with extensive handstitching; add patch of original nineteenth century tubular lace.

Condition: All structural and ornamental components now separate.

Action: Handsew ornamentation to front panel. Handstitch the cap's three main panels together, using original stitch-holes wherever possible, and notes on sewing patterns and stitch lengths taken at time of disassembly. Handsew regimental lace atop seams. Handstitch pompon at cap's apex.

Condition: Fabric missing at base of front panel (cut away as part of the nineteenth century reconstruction).

Action: Salvage green fabric from seam overlap of upper rear panel with lower; trim and transplant to cap front's lower edge. Secure with handsewn blind seam, backed with woolen tape. Use scarlet fabric salvaged from a nineteenth century British uniform to extend running horse and “Nec Aspera” panels; blindstitch and back, as with the green facing material. Replace salvaged fabric at seam with new.

Condition: Mitre's original strawboard-and-cane stiffening frame removed during nineteenth century reconstruction. Materials substituted at that time now disintegrated.

Action: Construct replacement frame of museum board (a pH-neutral substitute for the original, highly acidic strawboard) and Spanish cane. Use woolen panel dimensions, seams, and wear patterns as a guide for this construction's dimensions. Paint finished frame with acrylics, then create an acid barrier via application of four coats of Polyurethane varnish. Friction-fit frame within mitre. Note: Although it seems strange the the top two inches of lace-covered side-seams are concealed behind the front panel's apex, this placement is mandated by the shapes and placements dictated by original seams and wear patterns. In short, this is exactly how the original appeared.

CONSERVATION/RECONSTRUCTION RECORD, 30MAY13, p. 5 of 5

Condition: Lining.absent.

Action: Construct lining of vintage natural Belgian linen, of appropriate weight and weave, handwashed before use. Handstitch in place with running stitch around perimeter using vintage linen thread. Note: the lining's two structural seams and single dart were machine-sewn with cotton-wrapped polyester thread in a blindstitch, to avoid any potential for confusion by future examiners.

Final Action: Steam, bone, and towel overall.

Photography: All actions were extensively photographed. Compact disk is included with this report.

References: After extensive research, it eventually became apparent that eighteenth century British mitres are poorly documented and no contemporary scholar could be classed as expert in the topic. A very brief but helpful article by Robert Henderson, titled “The British Grenadiers and Their Mitre Caps” is readily available through several sources online, and appears to contain no factual errors or assumptions. The same cannot be said of Matthew Keagle's paper, “This is the Cap of Honor,” presented at the Material Matters Conference. Also easily accessed online, this piece is a pseudo-academic take on the topic, which borders on the absurd in some of its assumptions and claims. The previously-cited work, British Redcoat, contains some additional discussion and fine illustrations of mitres and the uniforms with which they were worn. Too, an online survey of Google's “Images of British Grenadier Mitres” is instructive. The very few remaining examples of this type--several of which are militia, and most of which are officers'--provide interesting comparisons. The various reproductions depicted online appear to be universally bad.

Artifact's Significance: Our researches indicate that this mitre is one of perhaps a dozen known original British Army examples dating to the eighteenth century. Of that number, few are enlisted versions, and no other examples from the Queen's Own Regiment appear to have survived. Too, the fact that this restoration project entailed complete disassembly of an original cap enabled rare opportunities for study. This documentation--pertinent especially to the construction of accurate reproductions--is now housed in the Turner, Laughlin & Associates archive.

Conservation Recommendations: Given this piece's extreme rarity, physical security--protection against theft--assumes more significance than is typically the case. Aside from this protection, every effort has been made to ensure that this mitre survives for another two or three centuries. So long as the usual cautions about lighting, handling, and fluctuations in temperature and humidity are observed, this piece should require no maintenance into the indefinite future.